Allan Shaw is a former bike messenger, a bikepacker and storyteller. He runs his own cycling cap business called Gay’s Okay, where he makes LGBTQ-friendly cycling caps to celebrate and encourage more diversity and visibility in the world of cycling. Originally from Scotland but currently located in Mexico City, Allan thrives on extending his limits, blazing new trails and being a passionate observer of the world around him. In this story Allan talks to us his experience racing this years Tour Divide.

What is the Tour Divide and what makes it special?

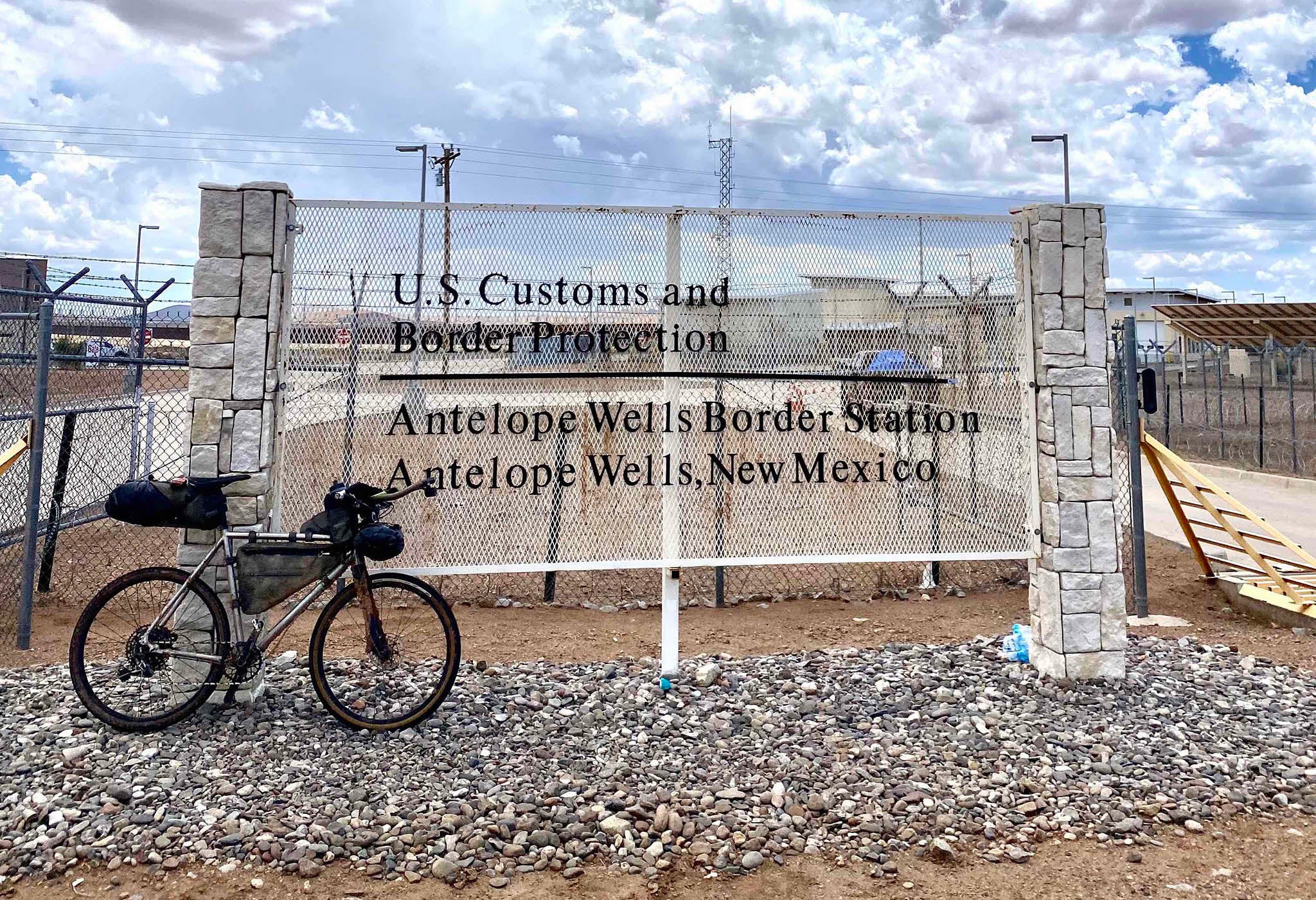

The Tour Divide is one of the world’s longest off-road ultra-distance bike races. Following the well-established Great Divide Mountain Bike Route, the race follows the Continental divide of the US and Canada from Banff, Alberta to Antelope Wells, New Mexico. Stretching 4300km and covering over 45,000m of climbing, the route is beautiful, diverse and at times exceptionally remote and isolated. It is a race that demands a high-level of skill, endurance and perseverance, and in many years’ races more than 50% of the start line fail to make it to the finish line.

How did you decide to compete in this year's Tour Divide and how did you prepare?

For me it was a long and tough journey to the start line of Tour Divide. After competing in last year’s Silk Road Mountain Race I had dreamed of Tour Divide being my next big race goal. Then, at the end of 2021, I was hit by a truck while out riding in the remote backroads of Mexico, where I live. I broke my pelvis in two places, as well as my femur and some other injuries. It was my lowest and most perilous circumstance physically in my life, requiring 4 surgeries and a complex recovery period to get me back to any level of normality. Tour Divide, for me, became my recovery goal. Something concrete to aim towards, to focus my energy on and keep me motivated. I started walking unaided again at the end of January, and started riding my bike again only at the end of February, a little over 3 months from the start of the race. It was only in early May that I made the decision I was definitely going to give it a go. Many racers I met before the race had asked me how my training had gone, and given the enormity of the race ahead, it felt kind of mad to tell people that I’d actually been in a wheelchair just 5 months earlier.

But what I lacked in physical prowess I knew I could make up for in my level of experience. I’ve crossed continents and raced ultra-distance many times in the past. I knew I could think on my feet, spend endless hours in the saddle and put up with plenty of discomfort after the year I’d had.

What were your top 3 best moments on the trail?

For both the good and the bad times, I think it’s important to think of them as moments and not days. I don’t think of the experience in terms of good days and bad days, the days are so long that there is a generous sprinkling of good and bad moments every single day out there on the trail. The key is to remember how temporary everything is, to forget about the bad times as soon as they are over, and to hold up good times as shining examples of exactly why you are doing it.

The famous Brush Mountain Lodge is a mecca for all cyclists either racing or touring the continental divide route. The compassionate, kind and generous host Kirsten is big on hugs and has ample snacks, food, beer and sleep space for any and all cyclists who pass through her remote and mountainous part of Colorado. The space is charged with the energy of so many racers who’ve come through over the years. It’s a great place of respite, a warm shower and an even warmer conversation, and Kirsten accepts only donations of what you can afford. The place has a family feel, which is so comforting so far into the race. The day I arrived at the lodge I had ridden 240km and could not have been happier that I was able to time my ride so I could justify a night’s sleep at the famous institution, and it ended up being one of my favorite nights of the whole trip.

• Great Basin

The Great Basin of Wyoming was one of the sections of the route I was least looking forward to, and then ironically ended up being one of my very favorite sections. It is a section of over 200km without any access to water or other services, in the high altitude desert plains of central Wyoming. It is infamous for, at times impossible, headwinds, rain and isolation. It’s the section people tell you you should just put your head down and get through.

I arrived at the edge of the Basin after having to take an early finish the previous day to wait for the bike shop to open the following day. I had some very curious issues with a loose front hub and drivetrain issues, and had gone to sleep worried I was going to lose a lot of time and spend a lot of money fixing things. In the end the nice people at Geared Up in Pinedale told me what I was kind of hoping, that it would be a time-consuming and expensive fix, but that it was pretty likely things would hold together and not get any worse if I just kept going. I am not adverse to taking risks, and went for that option, got on the road before 11am and was in the best mood to be pushing out of town. I managed to push out over 200km into the Basin that day, and I enjoyed the most spectacular sunset and sunrise of the whole trip. The empty, flat and expansive desert landscape felt powerful and personal. I was blessed with favorable conditions and it felt like a good omen for the rest of the race, like the worst was finally behind me.

• Finish Line

It is undeniable that getting to the end of such a long race is a huge moment, and with the difficult terrain and unpredictable conditions it’s one that can feel like a long way off even right up until the last day. While you watch racer after racer drop out, and the road ahead of you seems unending, for the longest time it’s better to completely forget about the finish line and about how it might feel to get there. I decided to give myself a shorter 130km day on my final day, stopping the night before in the desert to enjoy one last night camping (there was a crazy storm, tarantulas and mosquito bites, but that’s another story) so I arrived at the finish around midday. After having pushed myself so hard to recover from my accident and then push myself the whole race so I could reach my grand goal, it was a lot of emotion at once when I suddenly saw the border pop up on the horizon. The famous sign post everyone takes their picture at. The scale of the achievement, the enormity of it, hit me all at once, and I was overcome with one of the deepest senses of pride I have ever felt. I had a good cry, I will never forget the feeling.

What were your top 3 toughest moments on the trail?

This race is challenging on an almost permanent basis. The whole idea is you push yourself every single day, further than you think might be possible. With that in mind there are tough moments every day, and those tough moments teach you a valuable lesson on how you can endure hardship. In that sense I'm grateful for many of those tough moments, but it can also make it tricky to pick just three!

• Richmond pass snow

Probably the most infamous part of the race, the part of the race that made the local news under a headline like “Crazy cyclists rescued from Snow storm”.

I was outside a Gas Station in Columbia Falls when I bumped into Nick and David. To my surprise, they told me there was a massive storm coming our way, and that it would rain for more than 24 hours and fall as snow on the next mountain pass. Without any cell phone service I was committed to being prepared but blissfully unaware of whatever weather conditions lay ahead. Sure enough the rain started that afternoon. I found another racer Sandro who’d pitched his tent by about 9pm. Though it was a little earlier than I wanted, camping in groups ended up at least feeling a little safer in bear country. Another racer, Markus, ended up joining us and after setting up tents in the pouring rain, we all hoped it might finish around mid-morning, but oh how wrong we were. The following day we rode along together in the same pouring rain, after around 50-60km we started the big climb towards the pass with no idea what to expect. All of us already soaked through, at some point we bumped into a forest ranger who showed us an impressive map layout on her iPad and told us to be careful, it had snowed all night up there.

Another 10km up the trail we hit the snow line, fresh powder, slick and cold. It was still rideable for the first few kilometers and I found myself remembering the days I worked as a bike messenger through the winter in Toronto. I could do this, it wasn’t so bad. Then, all of a sudden, our route took a sharp left turn onto a hiking trail and everything changed immediately. The depth of the snow was well above the knee and there were no signs any other racer had attempted it in the last few hours. Lucky to have each other, we started walking. It was exhausting traipsing through the fresh snow with fully loaded bikes. We were sweating and soaking, the perfect storm for getting hypothermia in conditions like this. At some point I paused, checked the route and realised there was probably another 5-6km of this, which would take hours. Hours during which nothing could go wrong, no tiny accidents, rolling ankles, falling. Anything goes wrong and it would very quickly turn into a very serious situation. We kept our heads down and kept moving, telling funny stories and keeping each other's spirits up, but make no mistake, we were all pretty scared to put ourselves in such a situation. The feeling of relief when we noticed the level of snow significantly reducing was so palpable, I almost screamed in delight. After hours of uncertainty we were clear. Then there was the descent, which after so much exertion was freezing cold to whole new levels. When we made it to the next town, around 7pm, we immediately decided that was enough for the day and got a steak dinner and found a place to sleep indoors with much needed laundry and showers.

It had all been going so well that day. I had comfortably achieved all my small goals, crossed through the mighty Gran Tetons national park and was way on target to make it over one last pass and camp before the mammoth Union Pass. Then it all changed on that last pass. It started raining, which wasn’t a big deal, until the conditions of the road turned to loose, thick mud that clogged up my wheels to the point they refused to turn. I aggressively shoved my bike through the grass for a long time till it was rideable again, the trail then rejoined the road for most of the rest of the climb. There was a small gas station and I used its hose to rid my bike of an impressive amount of mud, coating everything. I continued on towards the top of the pass, now getting dark and really rather cold. The rain switched to snow as we gained altitude, got thicker and made it hard to see ahead through my headlamp. Near the top of the pass the route left the road and continued on dirt for the last few kilometers, with sections of snow to walk over but mainly that same thick mud from earlier. It was very VERY slow-going. I loaded my bike onto my shoulder and traipsed through the mud step by step. The uneven and slippery surface made me slip and fall a number of times. At some point I also sunk into deep mud and when I ripped out my foot my shoe came off, and I then had to dig in the mud to retrieve my shoe. It was truly as laughable as it was brutally hard. It was pitch black, snowing and I was filthy. I knew it could only be another 500m to the summit, but the previous 2km had taken me more than an hour. I couldn't decide whether it was really still worth it to keep moving or if it was just silly at this point. I checked my watch and saw it was almost midnight, and decided to stop right where I was, throw up my tent and wait for the first light and hope for better conditions. I knew it would be cold but I was confident I had good enough kit to withstand it.

Overnight it got down to -8c, my tent and bike bags were covered in frost. It also turned out with the magic of daylight I could see the top of the pass was barely 200m from where I pitched my tent. However, the worst decision I’d made was to ditch my bike without clearing any of the mud from the tyres or frame. By the morning all the mud had frozen solid to the bike and it was impossible to move the wheels or turn the chainring. I ended up spending over an hour using a tent peg as an ice-pick as I carefully and meticulously chipped away as much of the mud as possible to get the wheels moving. I felt resourceful, but it also felt just so silly. Once I was able to get the bike moving and I got over to the other side of the peak, within five minutes the sun was shining, the trail was gorgeous and the rest of the mud easily dropped off the bike. It was a moment I really did not enjoy, but I did appreciate my own reaction to the situation, to just get on with it, accept it sucked and still laugh at how ludicrous a situation it was.

• Fucking my hub NM

What many people know about me is that, despite spending the majority of the last ten years on a bicycle, mechanics is a topic that simply does not interest me. I understand how things work and how to keep myself moving, but above that it’s a language I have no real interest in learning. This is always my main concern on long races, what if my bike breaks and I don’t know how to fix it? It’s always in the back of your mind. And in this race, I ended up riding with a loose front hub for more than half the race. Partly because it really didn’t seem to get very much worse over time despite not being at all careful with it, and partly because I was afraid to spend so much money on replacing a whole front wheel. I was okay to roll along a little broken, as long as I was rolling. One evening in New Mexico, just 600km from the finish and at the end of a 295km day, I rolled through a thick dirt puddle and 500m further down the road I felt resistance in the front wheel. When I hopped off to have a look I could see my front hub was completely seizing up, taking the cables of my dynamo with it. Something had lodged in the hub and stopped it from turning. I was 12km from a cheap motel in a tiny town by the highway. No bike shop, it was late and my brain was foggy from such a long day in the heat. I made the, very dumb, decision to loosen the hub and gently slow roll into town with the axle rubbing on the inside of the fork. At the same time I messaged my two best mechanic friends to ask for advice, did some frantic googling of the closest bike shops and realised my only option might be to hitchhike to the state capital Albuquerque, a potentially massive delay just a few days from the finish, a huge disappointment. I limped into town with my broken bike feeling a bit defeated, wishing I could come up with a smart solution but knowing that my brain was too fatigued to figure anything out. I got the keys to my room, took a shower, sent a few more stressed text messages and went to sleep, deciding to get up early the next day, get to the Gas station and attempt hitchhiking.

The next morning I decided to tighten down my axle as much as I could and put a bunch of pressure on the wheel to spin as I hopped on and made the three-block journey along to the Gas station. At first the wheel made some wild screeching noises, but the resistance reduced. By the time I got to the Gas station I had managed to dislodge whatever was blocking the hub and the wheel was seemingly rolling pretty freely again. Now I was faced with a rather huge dilemma, take a huge risk and keep rolling the last 600km on a hub that is clearly very broken, or lose potentially a whole day or two hitchhiking hundred of kilometers across the state to spend a chunk of money to get the bike to a respectable riding condition. With a lot of inner-conflict I decided to go for broke and take the risk. The whole race had been a risk and it was too close to take the safe option at that point.

Very fortunately the bike held together good enough to make it to the finish line with no further dramas, but it was in a very rough state!

What were your top 3 items you couldn’t have lived without?

• Headphones

Distraction is a true art form. Pulling your mind's attention away from its physical discomfort and niggling doubts is a constant challenge. For me listening to music and podcasts is an indispensable tool for distracting the mind and reinforcing a positive attitude. Also being able to call friends and family from the saddle during the periods where I had cell service was such a boost.

• Gas Stations

I will happily admit that I’m a huge fan of the great American Gas station. For convenience, for frequency, for consistency of candy, sodas and trashy food. For a race like this it is a haven of Calories, which you desperately need. I have a real sweet tooth and a guilty pleasure for fast food, and I entered every Gas station with such delight to buy all the candy, hamburgers, sodas and iced coffees I could possibly fit. I was making the joke that a good race sponsor would be Haribo, because you end up consuming so much candy. At some point Supermarkets became too confusing a level of choice, Gas stations had everything you needed in the perfect sized outlet.

• Gay’s Okay Cap

I’m very proud of the company I’ve built (gaysokay.eu) and the impact it has had on the world of cycling and its visible representation of LGTBQ people. As one of the very very few LGBTQ ultra-distance cyclists I always want to represent and fly my flag proud, to encourage more people to feel included, and wearing one of my caps is an integral part of that. Unfortunately, I ended up forgetting to bring a cap, damnit! However, in my desperation to represent LGBTQ cyclists across America I managed to find a blank cycling cap the day before the race and used a sharpie to write GAY’S OKAY across the brim, which I wore all the way across the country.

What pair of shoes did you use and how did they perform?

• Gran Tourer II

I knew this was QUOC's signature gravel shoe, versatile and comfortable, so it seemed like a no-brainer to pick this shoe for the trip. I wore these shoes for sometimes up to 19 hours a day without taking them off and they were consistently comfortable. They dried quickly after getting wet and dealt with all the pressures of the trail super well. I also did an exceptional amount of walking in these shoes and had no complaints in terms of foot or ankle discomfort (not that I’d recommend these as hiking shoes, but sometimes the trails demand it). The shoes saw snow, rain, mud, sand, rivers, rocks and more and are still in great condition after all that, ready for their next adventure.